It felt like my gut was an industrial washing machine set on “agitate,” churning furiously and steadily. It felt like I had two weasels in my midsection, their claws braced into the walls, trying to tear each other apart. It even reminded me of the classic sci-fi B-movie “The Hidden,” in which an intelligent but malicious alien slug parasitized a succession of unfortunate human hosts; when the slug had almost used up each host, it rumbled much like the mother of all cases of indigestion. Really, it reminded me of that.

I’m not describing the symptoms of giardia. I’m describing the medication prescribed as a giardia treatment to eradicate it. And, as it would turn out, the medication, for all its harshness, did not even completely eliminate the giardia infection.

Let’s go back to the beginning. I didn’t even know, at first, that I’d picked up any microscopic organisms. About a week after returning from a week-long backpacking trip in 1991 (during which time I’d carefully treated all water with iodine tablets–double-strength, in fact) I experienced what I presumed at the time to be a mild case of the flu. It was four days of intermittent and slight fevers (though no vomiting) and I didn’t wander far from a bathroom because of the explosive diarrhea. Then it went away.

A couple of months later I was browsing through books on backpacking when an amusing title caught my eye: How to Shit in the Woods, by Kathleen Meyer. Finding a list of symptoms for something called “giardia,” I ran down that list: “Had that, and that… but not that… have that now. Hmmm?”

Reminder: This article is not a replacement for professional medical advise. It is largely the experience of one individual. If you are having a similar experience or believe your symptoms indicate you have Giardia, please seek professional medical attention!

Giardia Symptoms

The listed giardia symptoms, as graphically and specifically described by Ms. Meyer in her book, were:

- A large volume of foul-smelling, loose (but not watery) stools seven to ten days after ingestion, accompanied by abdominal distention, flatulence, and abdominal cramps, especially in conjunction with wilderness or foreign travel (other sources to consider are domestic dogs and cats and preschool daycare centers).

- Sudden onset of explosive diarrhea seven to ten days after ingestion.

- Nausea, vomiting, lack of appetite, headache, and low-grade fever.

- Acute symptoms can last seven to twenty-one days and may become chronically persistent or relapsing.

- In chronic cases, significant weight loss can occur due to malabsorption.

- In chronic cases, bulky, loose, foul-smelling stools may persist or recur—they may float and be light in color.

- Chronic giardia symptoms may include flatulence, bloating, constipation, and upper abdominal cramps.

Many individuals, unknowingly, are asymptomatic passers of cysts.

Giardia Prevention

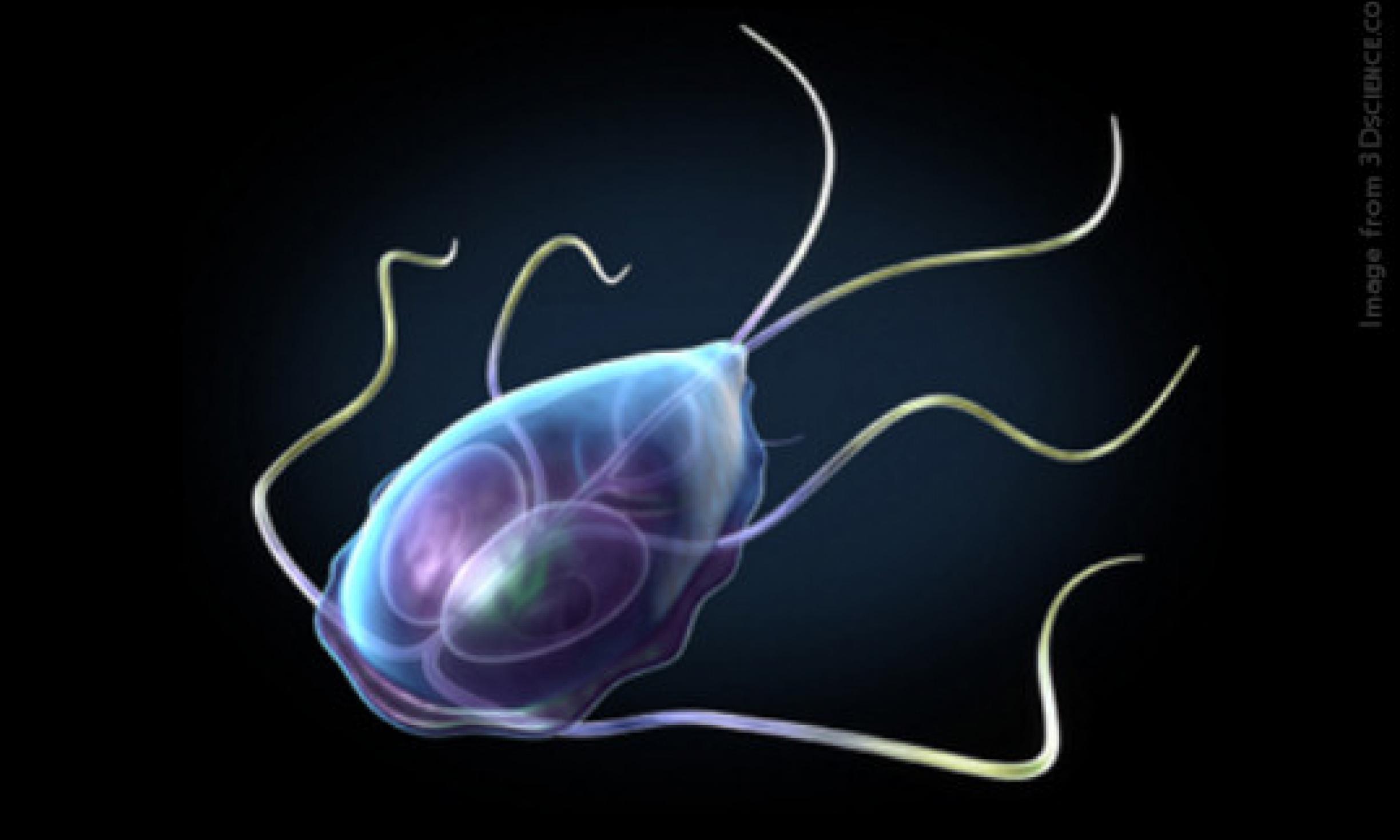

Giardia lamblia is a single-celled protozoan, and the giardia cyst is the dormant stage, the hardy form in which it exists in the environment, and, so, the form in which it is ingested. Meyer’s book is well-worth reading, for its discussion of how and when giardia infection became such an issue for concern, particularly for backpackers, as well as common vectors of ingestion. And because it’s a well-written, informative, and wryly amusing book about a subject that many would rather not discuss.

So, I hadn’t had all the giardia symptoms, but I recognized enough of them that I figured I’d better get it checked out. Fortunately, though I was working part-time (in a hospital cafeteria) I had medical insurance. I described my symptoms to the gastrointestinal specialist, and he agreed that I likely had giardiasis (commonly called giardia). Lab work (a stool sample) confirmed it.

The doctor told me some interesting things about giardia. Some people’s systems can completely eliminate the critters (it is, technically, an animal). In others, the protozoa will encyst themselves somewhere in their host’s intestinal wall and go dormant.

This doctor had just finished treating a patient in his eighties for giardia symptoms; the fellow had no idea how he’s picked up the parasite. The last time he’d drank anything but city tap water had been on a camping trip thirty years prior—the giardia cysts had survived that long (they may well have resumed their trophozoitic, active stage from time to time, and there may have been no symptoms, or they may have gone unnoticed).

Giardia Treatment

The idea of potentially being an unwitting carrier (and passer) of the giardia cysts scared the crap (that’s what we’re talking about here, right?) out of me.

The giardia treatment medication prescribed for me was to be taken after full meals. A pharmacy tech described it as being in the same class of meds that they give people in the advanced stages of syphilis. As he put it, “It basically finds anything that’s non-body and flogs the crap out of it.”

Well, it did feel like there was a flogging going on. In my gut. Constantly. At one point I took my dose with less than a full meal; I ended up in the ER, clutching my gut, and doubled over in pain. What made it even worse was that I was treated in the ER by a young, cute, resident physician that I’d been kind of sweet on but there she was, with a finger up my butt checking for internal bleeding. I could never look at her in a potentially romantic way again. Hell, I could barely meet her eyes at all.

After the turbulent two-week course of the medication, my poop didn’t suddenly look normal again. In fact, what I was passing resembled a fine brown powder in solution (gone, along with the unwanted parasites, were the intestinal flora, the beneficial bacteria that we all have—and need—to aid in digestion. I didn’t fart for a couple of months; the doc hadn’t said anything about this. I figured it out myself and started eating as much stuff with active cultures as I could find. Very gradually, the farts and solid poop returned.

Two or three years later, the symptomatic soft light-colored floaters returned—just the single symptom. (I’d continued to backpack a lot, but had switched from iodine tablets to a water filter that was guaranteed to remove the giardia cysts) This time the lab tests came back negative, but the doc recommended the same treatment anyway, saying that sometimes the tests miss the giardia infection. I did so. Goodbye, farts….

Last June, about ten days after my first trip of the season, the ‘floaters’ showed up again, along with a slight fever for a day or two I was perplexed: I’d been diligent regarding my water sources. My walk had covered about thirty-five miles of the Olympic National Park coastal section from Rialto Beach to Shi Shi. I do it every year. On earlier trips, the dissolved tannins in the slow-moving streams had clogged my water filter so quickly that it hardly was worth using. And boiling all your water takes up a lot of time and fuel (then you’re stuck with drinking hot water in June). So I opted for the masochistic speedy-but-heavy option: I filled all my bottles at the campground faucet near the trailhead at Rialto. The next evening I hiked inland to Lake Ozette and reloaded at the campground there. On the last night, at Shi Shi, I carefully boiled spring water for ten minutes (I’m aware of little things, like not dipping water with the pot I’ll be boiling it in, as water clinging to the lip of the pot will not boil, carefully pour it in from a separate container—an empty pop bottle whose only other use is dowsing campfires. And sanitizing hands after contacting untreated water. Even a stream-soaked kerchief on your head can trickle water into your mouth, or water swallowed while swimming—these are a few of the vectors by which the giardia can enter your system).

I called park officials to find out if the purity of either of the two faucets I’d used had been compromised. There had been no reports. Besides, it didn’t seem like I’d contracted a whole new case—I was just showing a symptom or two.

I conferred with a friend who makes her living as a wildlife biologist. She said that her ex-husband had had similar recurring episodes of giardia infection—he’d called them “echoes”—which didn’t go away completely, despite repeated treatments by an MD, until he sought treatment from a naturopath. It was my friend’s contention that the way the AMA treats giardia infection does not completely eradicate the protozoa, particularly in its dormant cyst form.

First, I went back to my hospital for lab tests. Again, the tests were negative, but the doctor was ready to prescribe the same medication. I’d been thinking about “The Hidden”, and agitate cycles, and weasels in my gut. And “echoes.” I told the doctor of my hesitancy to put myself through it all again, especially if I was in doubt that it would be effective. I told him of my interest in giving a naturopath a shot at it. To his credit, my doctor responded, “Either one can work.”

I gave the naturopath’s assistants an appropriately clinical synopsis of my parasite saga (with the weasels, but without the malevolent alien slug). When the doctor arrived he listened to their summation, and then gently but thoroughly palpated my abdomen. Within two or three minutes he found a spot (just south of the bottom edge of my ribcage on the right side) that was tender. He asked me how long it had been tender; I couldn’t recall. I was tensing it to protect it from his fingers, and he asked me not to resist so he could really get in there. His probing wasn’t painful, but as he carefully investigated the area I realized that the area had been tight and sensitive to pressure longer than I could remember.

“That’s where they are—up high,” he pronounced.

I explained my theory to him—that the giardia cysts had been with me ever since my first exposure, and that it simply flared up when my immune system was compromised—like when I wore myself down by covering fifty miles in two-and-a-half days.

“That would do it,” he agreed.

A subsequent stool sample tested positive for giardia, and a treatment plan was devised. As the herbal products prescribed are not controlled substances, my medical insurance would not cover them. But they were not expensive; a couple of them didn’t cost much more than my pharmacy co-payment would have been.

There were three meds: two were antibiotics, and the third was described as a ‘probiotic’—to restore and maintain the proper balance of the good cooties—the intestinal flora—while the antibiotics were ridding me of the giardia. I was to take the antibiotics with my meals, and the probiotic, before bed.

The giardia treatment was not traumatic, or even uncomfortable: the agitated weasels and alien slugs didn’t come with the package. I didn’t lose my God-given ability to fart; I didn’t crap brown silt for weeks afterward. Nor did I end up in an ER, getting a finger poked up my rectum. I researched the contents of my antibiotics: one was made from the roots of two varieties of a plant which has been used by the original inhabitants of my area to cure stomach ailments; the other was composed of two Old World plants (grown locally) used traditionally for the same sort of ailments.

You have doubtlessly noticed, perhaps with some annoyance, that none of the medications used in either treatment have been mentioned by name. That was intentional. In this time of unscrupulous prescription filling via the internet, I’m certain that the med the AMA generally uses is easily available. And since the herbal products are not even controlled substances, they’d be even more easily available. But consider the old axiom that all medicines are poisons. Self-diagnosing and treating intestinal parasites with antibiotics are not a job for the amateur.

And the symptoms for giardia are nonspecific; there are plenty of other problems that can exhibit the same, or similar, symptoms. You really need to consult a physician (which sort is up to you) and submit a stool sample.

In the meantime, to avoid ever acquiring this parasite: the primary vector by which giardia is contracted is through ingesting water, or food, contaminated by infected human or animal feces. Boil all backcountry water—regardless of how pure and pristine it appears—for five minutes (longer at higher elevations). The only other option is to use a water filter with an absolute pore size of at least 1 micron, or one that has been NSF-rated for “giardia cysts removal.”

Am I clean? Am I giardia-free? I don’t really know. My poop, at long last, looks normal (there’s nothing quite like finding out you’ve been a carrier of an intestinal parasite for a dozen years to inspire you to keep an eye on what’s in the bowl—I don’t know, maybe it’ll pass). I’ll feel more confident after another summer of pushing myself past exhaustion. I’ll see what happens.